Paul Eade Kansas City Country Club Plaza Art Gallery

American cities changed drastically over the course of the 20th century. In a word, they suburbanized. Ane style in which to see that is to look at urban form, that is, how streets were laid out and how buildings were set upon lots. From the gridiron plans and cheek-by-jowl buildings of the late 1800s to the suburban cul-de-sacs blanketed past grassy lawns common past 2d one-half of the 20th century, urban form reflects larger shifts in the legal, economic, and cultural aspects of urban development.

Kansas Metropolis, like other American cities, added new suburban-style developments at its edges during the early decades of the 20th century. What makes it a unique case for understanding this shift is the character of Jesse Clyde (J.C.) Nichols. Born in Olathe, Kansas, in 1880, Nichols had a career that spanned the beginning half of the 20th century, and included transforming thousands of acres of land into a planned suburban customs. That piece of work can be divided into two parts: the Country Club Plaza was one of the earliest shopping centers in the country, and information technology made Nichols well known both in Kansas City and among American urban historians. He is also known for the Country Club District and its suburban landscape of curving, tree-lined streets filled with gracious, middle-class homes that has had surprising longevity and stability.

Nichols advocated for a suburban model of urban form, and in his expansion from aristocracy, high-cease homes into the eye-class market place for residential subdivisions, he linked the practice of urban development to its theory. He both congenital cul-de-sacs, working with landscape architects, and advocated for them, putting his techniques for state development first in forepart of professional audiences, and later in front of federal policy makers.

Thus, Kansas Urban center, while perchance non every urban historian's paradigmatic instance, is nevertheless ideal for understanding the resilience of the cul-de-sac as a format for urban development. Nichols positioned the Country Club District as a model for other cities to follow, in essence elevating suburban-fashion growth as a pick that developers could make to supersede the gridiron model. His unseen innovations in land evolution techniques gave the format staying power and enabled private, market-led city planning.

Nichols'south story as well offers a contrast to the grittier side of Kansas Metropolis in the 1920s. While "Dominate" Tom Pendergast ran the old Kansas Urban center, the smoke-filled gridded streets of business and industry'south rough edges, Nichols presided over the sylvan landscape of tree-shaded lawns and curving boulevards at the city's quickly expanding periphery. Though the 2 sides of the urban center were of course linked (Tom Pendergast, for example, enjoyed the charms of Nichols'southward State Club District in a house he built for himself there), different urban forms, modes of development, and legal foundations underpin the autograph nicknames (urban vs suburban) that have codified discussions about the built environment ever since.

Nichols's career began in the opening years of the 20th century, a fourth dimension when city planning and mural architecture were fields only coming into being as professional enterprises linked to city evolution. Those looking to plough a plot of dirt into profit-maker wanted greater control over the process and increased odds of success. City builders and planners had struggled over how to guide development, and two ideas rose to prominence in the early on 20th century: zoning and human action restrictions.

Zoning offered a public process—a authorities policy that could control land use and direct new structure to generally align with a broader metropolis plan. The deed restriction offered some other method—a private exercise, essentially a contract between heir-apparent and seller, that could control many things from state use to building setbacks. Deed restrictions are clauses added to the deed of a property that can put a multifariousness of limitations on that deed—from requiring buildings to be set back a certain distance from the holding line, to (historically) specifying the race of the inhabitants. As deed restrictions are a private machinery for decision-making development, real estate developers were swell to empathize what this could offer, and suburban developers like Nichols were at the forefront of exploring its possibilities.

Race and Real Manor

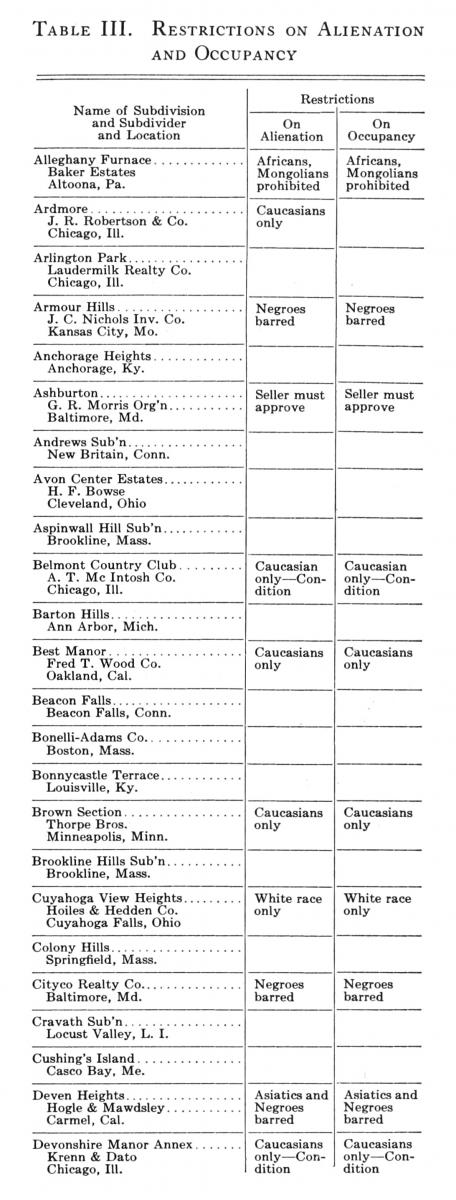

Deed restrictions are most normally known for their racially restrictive clauses, whose legacy reveals the intertwined human relationship between race and real estate. Racially restrictive clauses in deed restrictions produced an intentionally segregated mural that white power elites wanted for their city. This was non accidental, and the repercussions of this for the United States go on today. In 1948, a supreme court ruling (Shelley v. Kraemer) concluded the enforcement of racially restrictive clauses, just every bit other scholars have shown, that conclusion did not bring about an terminate to residential segregation, and structural conditions still enabled a racialized landscape to continue through today.

Nichols, lauded though he might be for the charitable work he did in the city, also actively helped construct the racialized landscape of Kansas City by putting racially restrictive clauses into the human activity restrictions on all the backdrop he sold. The practice of redlining neighborhoods, in which a federal agency rated neighborhoods for their creditworthiness, built upon this landscape of restrictions to construct the entangled prosperity and inequality of homeownership, existent estate, and race in America. Existent estate analyst Helen Corbin Monchow's 1928 book, The Use of Human activity Restrictions in Subdivision Development, instructed real estate developers on how to utilise act restrictions (also chosen covenants) to their all-time advantage, and in a chart, she includes Nichols'south restrictions on race for an area of the Country Club Commune, Armour Hills.

Nichols contributed to the give-and-take around deed restrictions in meaning means. When asked to write a brusque review of the volume that contained the nautical chart of racially restrictive clauses, he wrote a 12-page article expounding on his many thoughts on the topic. Piffling of the public give-and-take Nichols participated in directly described the systemic racism that developers actively created.

Deed restrictions did command other aspects of land evolution beyond creating racial segregation. A two-page, fold-out chart from a 1925 issue of Landscape Compages magazine shows just how many factors the deed restriction could control, including, for example, limiting hedge heights, prohibiting hogs, requiring building setbacks, and setting minimum construction costs. They became standard exercise across the land in suburban developments—part of the legal infrastructure on which suburbia is congenital.

Suburban Infrastructure

In the Land Club District, Nichols congenital suburban infrastructure. More than than constructing homes, turn-primal style, he laid roads and sidewalks, cached water and sewer lines, and subdivided state into lots. Much of this work was subterranean and contractual—infrastructural, in other words—but it also had a incomparably aesthetic component. What the suburb looked like mattered quite a lot.

Unlike virtually developers at the time, Nichols hired landscape architects to lay out his subdivisions and to design public green spaces on medians, esplanades, and other remnant spots of vegetation. Hardly large enough to authorize as park spaces, these enhancements were in some sense centre candy, busy with statuary and fountains, only Nichols saw them every bit much more: every bit aesthetic devices for ensuring stable property values, maintained through the legal device of the abode owners' association.

Nichols believed the aesthetics of curving lanes, bird baths, and shrubbery not only bolstered, just as well steadied property values, providing Kansas Metropolis with an expansive landscape that showcased his vision of private-market metropolis planning. Nichols did not see his investments in plant material as a sales tool for moving empty lots as much as he saw them as an infrastructure that would bring long-term dividends. In this way, leftover spaces gained productive value, signaling and ensuring through their aesthetics the high value of surrounding properties. This piece of leafy suburban infrastructure was simply another component of Nichols's system of legal and economical standardizations aimed at producing steady property values for his purchasers, insulating them from the dangers of investing in real manor, what he chosen "unstable merchandise."

Nichols was a atypical but key player in creating the cul-de-sac landscape of suburbia, whose designs and deed restrictions would afterwards be promoted past the Federal Housing Administration equally standards to follow. A leader in his field, Nichols regularly borrowed from the linguistic communication and techniques of city planning and mural compages to accomplish his projects, and he repeatedly and explicitly divers his work and that of other "real manor men" in relation to the discourse on city planning.

Nichols wiped any off-putting politics from metropolis planning discourse in his retelling of it, casting urban center planning equally a concern-friendly initiative that would piece of work together with developers to abound American cities. His human activity restrictions established self-perpetuating, private controls to development that became the model for other developers, forming the legal groundwork for private land use control, artful regulation, and an intractable urban fabric. Nichols capitalized on techniques from landscape architecture, paired with his own legal innovations, to establish and maintain in perpetuity the romantic, leafy-green artful unremarkably associated with suburbia. The unurbanized southwest edge of Kansas City in the early decades of the 20th century was the canvas on which he experimented.

Nichols's Sales Craft

Nichols began subdividing in 1904, having no feel in the business and little capital to launch his plans. He borrowed the equipment to put in the first curbs in the State Social club District and salvaged woods from a barn to build sidewalks. Those curbs and sidewalks were some of the kickoff of the physical "improvements" to the Country Club Commune – the name given to the assemblage of smaller, contiguous subdivisions Nichols adult piecemeal southwest of Kansas Urban center until his death in 1950.

Nichols employed landscape architects to pattern his subdivisions at a fourth dimension when about developers did not. As early on every bit 1907, Nichols worked with landscape architect George Kessler to subdivide a big farm he was purchasing westward of land that had already been subdivided. Afterward he would hire the begetter-son firm Hare & Hare to design many of his subdivisions. Landscape architects were an added expense that most developers avoided, just Nichols mined the techniques of mural blueprint to make his subdivisions more exclusive and more assisting. The expected signs of a landscape architect's manus—curved interior streets, minor park areas, sensitivity to topography, and a bureaucracy of roads—announced in Nichols'due south developments from an early date. Landscape architects were also adept at maximizing the number, and attractiveness, of saleable lots on a given piece of land. Put simply, Nichols hired mural architects to increase land values in his neighborhoods.

The role of mural compages in Nichols's work reflects a longstanding and meaning association between picturesque ideals and residential design. As part of the professionalization of the field of mural architecture, pushing away from associations of "feminine" gardening was cardinal to legitimizing the work of men in the field. But this gendering did not remove the picturesque aesthetic then commonly understood, so and now, as suburban. Histories of U.Due south. suburbia have shown how the picturesque represented a timelessness and escape from the metropolis and its industry. The landscape designs of suburbia held a cultural meaning intended to provide separation from the domestic sphere and stability against the fluctuations of mod capitalism; likewise, information technology connoted the aristocracy gardens of the English that secured cultural hegemony.

Equally scholars have observed of the picturesque suburban cemetery designs of the mid-19th century, the cosmos of a timeless, domestic space of permanence and rest for the dead explicitly countered the hustle of the unpredictable market in the gridiron city. (Indeed, one of Nichols's mural architects, Sid Hare, was a cemetery designer before opening his own mural architecture firm.) The soft edges, gentle curves, and lush greenery hid the harshness of the speculative market and suggested something of the sublime in its place. Nichols connected to build on these cultural meanings while finding new ways to operationalize the product of such landscapes. Economic exclusivity and enhancement of lot values was the goal: landscape architecture, the tool.

To further this aim, construction details were calibrated to concenter high-paying buyers. J.C. Nichols paved the roads in his subdivisions, matching his delivery to mural architecture with a commitment to automobiles. The curb design and size was important for keeping cars off lawns in these early days of the automobile. The well-paved roads and sidewalks illustrated readiness for the family auto in promotional textile. Nichols's 2 sons even worked on road-building and maintenance crews in the summers, learning to lay heavy stones equally base, breaking up that stone with a napping hammer, and "indelible the suffocating asphalt fumes equally they spread the macadam top." Explaining how the large-lot design improved automobility for residents, Nichols told the Ladies Home Journal in 1921, "In these days of the motor automobile you lot can whisk around these long blocks in a jiffy."

Nichols'south mural architects also used another kind of design—bronze fountains—to sell buyers a vision of high-end suburban living. The neighborhood'south traffic-directing street layouts created modest, postage-stamp sized parks, islands surrounded by roads. These Nichols turned into selling points by filling them with fountains and sculptures. He collected the art on trips to Europe, calculation to the full general cachet of the endeavor, and held receptions to unveil new acquisitions. More than than mere ornaments in the mural, Nichols believed these objets d'art established an aesthetic tone that reflected the street design, and helped build a long-term vision for the quality and financial stability of the area.

Nichols'south landscape architects used site design and street layouts to sell buyers a vision of loftier-terminate suburban living. Though Hare & Hare's practice would never exist equally influential as Kessler's, the house designed features in Nichols'southward subdivisions that reverberate a new approach to real estate development. Hare & Hare's Hampstead Gardens plat introduced curving streets and small, uninhabitable triangular parks at three-manner intersections to direct car traffic and add together greenery. Blocks were mostly oriented to run east-west, equally in Nichols's previous projects, accentuating the bureaucracy of arterial roads. The east-west orientation besides immune for ideal sun exposure on the majority of homes that would confront north-southward.

More than by and large, if a gridded city program would give equal importance to all roads, suburban superblocks create a hierarchy of roads—major arterials for faster traffic and smaller neighborhood streets for residential enclaves. By curving the roads gently, Nichols slowed traffic on them, and encouraged drivers to use the arterials instead of the indirect smaller streets. Curved streets, Nichols believed (in an repeat of the picturesque), offered an "ever-irresolute vista" that was "more pleasing to the eye," every bit his son afterwards recalled his begetter maxim on drives through the District. Unspoken just easily inferred is his dislike of the monotonous, gridiron, pothole-ridden city, conjuring too much the difficult edges of commercialism. By dissimilarity, his well-paved roads and sidewalks were all highlighted in advertisements for the District to illustrate readiness for the family motorcar.

Early in their collaboration with Nichols, Hare & Hare designed the high-end Mission Hills subdivision, a 240-acre evolution of large lots on the Kansas side of the state line. Platted in 1912, Mission Hills was bisected by a creek that divided the residential area from the country order and golf form to the due north. The traffic arteries that continued into the subdivision from the eastward curved to follow the topography and creek, creating the visual interest Nichols liked. One exception at the center of the subdivision was "Colonial Court," a block-long divided road with a formal planted median. Triangular parks at intersections were again laid out in accordance with the turning radius of an motorcar. Lots were very big, some with as much as 175 feet of street frontage, and varied in size. They were intended to draw high-paying buyers. Nichols as well planted thousands of trees in the subdivision between 1912 and 1919. Since the subdivision was in Kansas (not Missouri) and in an unincorporated area, all services—sewers, water, and electricity—were provided by the Nichols Company.

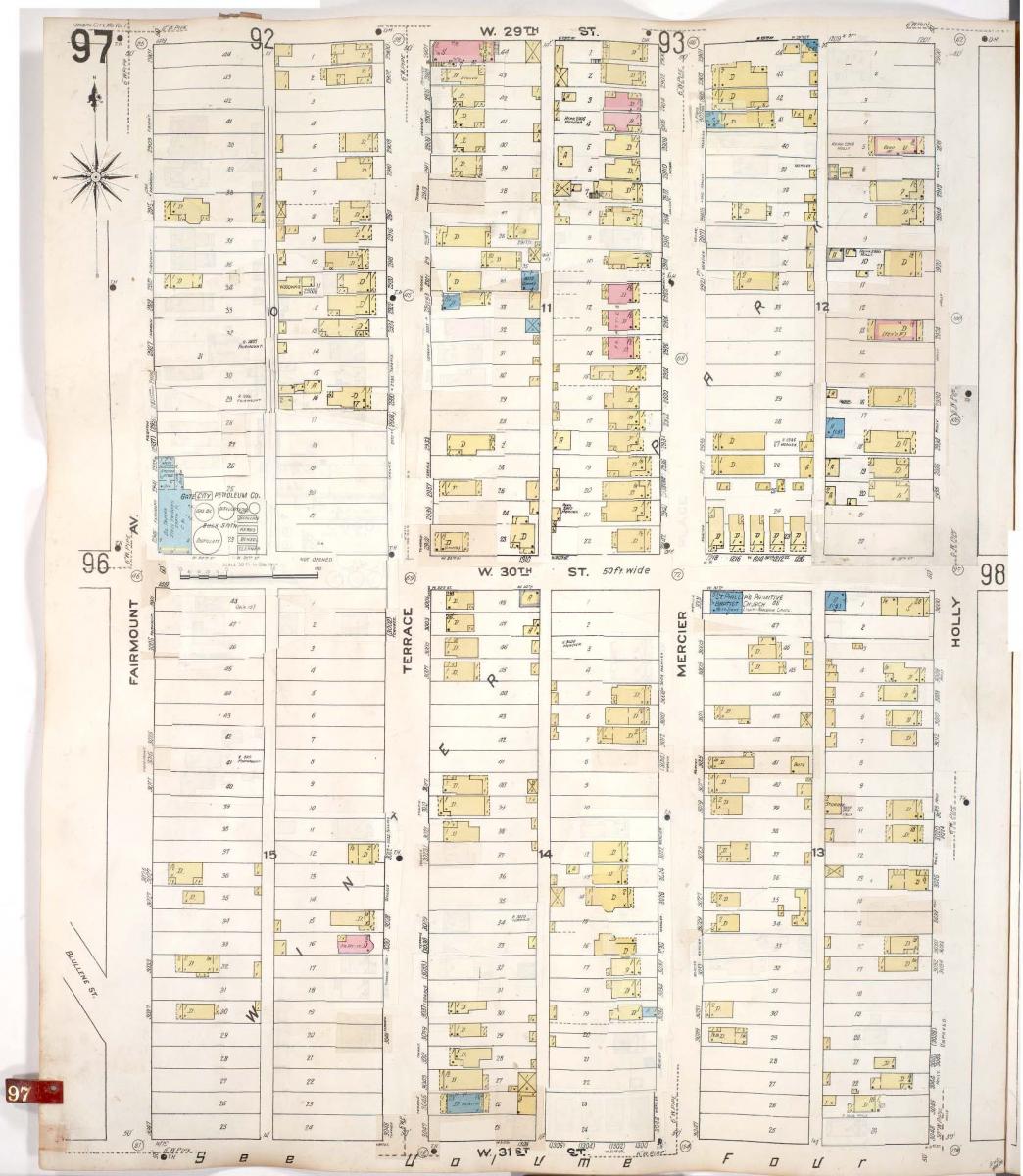

Nichols's picturesque schemes became more confident as fourth dimension passed. His seeming success in selling lots, the larger sites he caused, and the ongoing lack of city oversight on unincorporated land immune him to continue the experimentation. By the early 1920s, Nichols'southward street patterns regularly disregarded the preexisting grids inside tracts of land—atypical for residential development at the fourth dimension. In the Armour Hills development, Hare & Hare designed a subdivision that continued the numbered streets running roughly eastward-west on the site, but modified them to curve gently and break the grid's regularity. An aeriform photograph of the development early on in its construction shows a straight line of trees, as if drawn by a ruler, from the previous Jeffersonian filigree pattern that covered the site. Atop this lies a new layer, etched onto the site, in the contrasting curving street pattern that disregards the markings of the site's farming days.

Like other Nichols developments, Armour Hills's plat program responds to the relatively flat topography of the site and the lack of any outstanding landscape features by highlighting the slight changes in topography with the lines of the streets and transitioning from a regular, gridded street system on the western boundary to a more curvilinear scheme in the center, and so returning to a regularized street pattern at the eastern boundary.

Security of Investments

Landscape architecture was not enough in itself to maintain property values over time, then Nichols also looked to legal mechanisms to stabilize value and to further increase exclusivity, both racial and economic. Nichols promoted the utilize of deed restrictions to control state use, setbacks, racial demographics, minimum costs, construction standards, materials, colors, landscaping, and, thereby, aesthetics. On this he mostly copied developers of high-end subdivisions before him. But no other developer looked to extend and finesse this device to more than middle-form homes, and no other developer had found a mode to extend the life of the restrictions with automated renewals. Nichols did.

In the 1910s, Nichols actively participated in discussions amongst developers virtually how to make act restrictions lasting, as at the time it was unclear what mechanism would provide enforcement and what would happen when restrictions expired. Typical deed restrictions at the time would simply fade away, and just the rare committed programmer might decide to pay the bill for legal fees when a buyer broke their contract. Nichols worked toward and eventually found a way to make the renewal of restrictions automatic and to create an say-so to enforce deed restrictions in perpetuity.

As an enforcement machinery, Nichols invented the Habitation Owners' Clan as we know information technology, and information technology came about as a solution to the cost of maintenance that typically brutal to the programmer. While lots sold in a new subdivision, developers were on the hook for the cost of city services similar trash removal and for maintaining mutual areas. Upon buy of a property, a heir-apparent was automatically given membership to the association, which charged assessments based on lot size. The association's responsibilities included maintenance and upkeep of common areas and parks, as well every bit overseeing utilities and services like snow removal.

Nichols's primeval deed restrictions controlled state use past allowing only residential use; they controlled form past setting a minimum construction cost for the not-yet-built houses; and they controlled the urban textile by mandating setbacks from the street and orientation of the building. His Home Owners' Associations so continued the enforcement of deed restrictions and managing and funding the maintenance of the subdivision into the future.

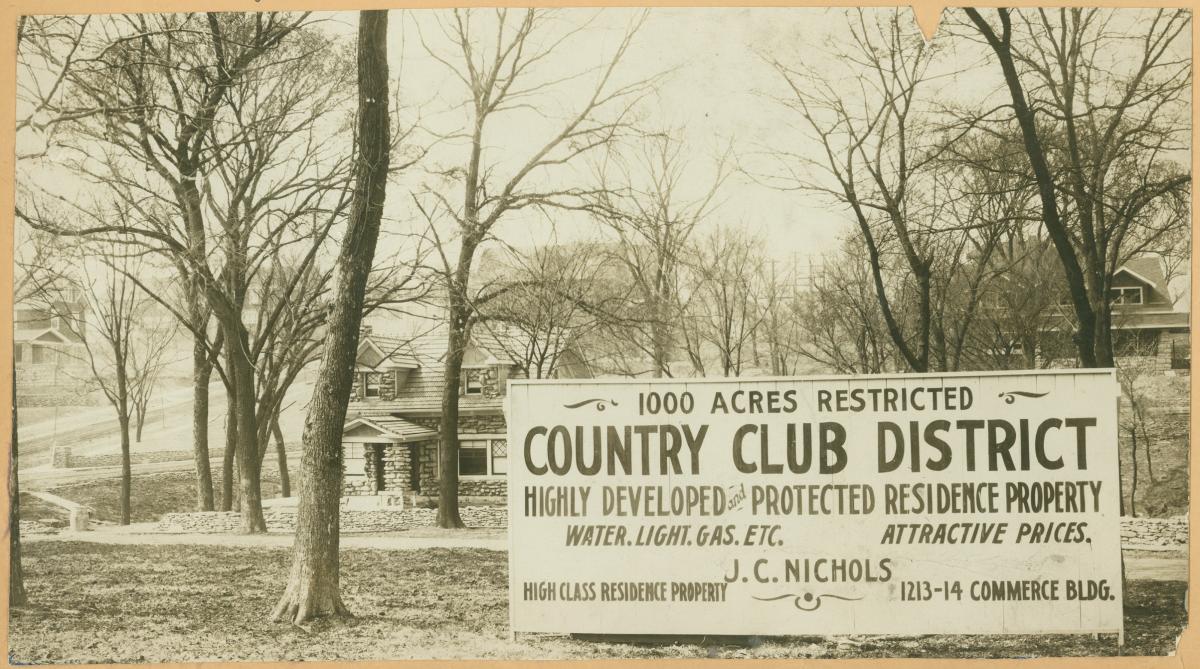

Building upwardly his holdings, Nichols had accumulated over 1,000 acres by 1908, and over the post-obit decades those acres were built out past abode builders and owners. Nichols began advertising his larger plans in the Kansas Metropolis Sun by highlighting the big size of the development and the deed restrictions as protection against market instability. "Have You Seen the State Club Commune? ane,000 Acres Restricted for Those Who Want Protection," the advertizement read. And in a subsequent visitor brochure: "In the Country Club District you are given the protection that goes with 'a 1000 acres restricted.'" The limitations on property use and buildings translated into good sales practices for the Nichols company. The language of Nichols's ads suggests the exclusivity accompanying a members-only order and reflected consumers' concerns that in a volatile existent estate market rife with speculators, their investment in a property might disappear. The substance of the restrictions—setbacks, common infinite, racial exclusion, and state use limitations—played off those concerns and were the key focus of Nichols's sales pitch.

Existent manor, the salesman Nichols once declared, was "unstable trade." He believed that the Country Club District was "a practical demonstration of the value of good planning, as is shown by its effect upon the banks and insurance companies, simply because they experience that past our planning nosotros are securing values, stabilizing values." Developers and bankers believed stricter restrictions were favored by belongings owners because they were designed to stabilize that "unstable trade." Without zoning regulations or human action restrictions, and without the authority of a city planning department, a home heir-apparent would have no bodacious expectations for the evolution of neighboring properties. Not merely would the bank be more likely to renew a loan on a covenant-restricted property, only baneful industrial or commercial tenants could non move next door.

These protections non merely contributed to segregation in housing, perpetuating racial injustice, but they also offered the programmer the obvious incentive of greater profit. Over the decades, Nichols'southward subdivisions accept held their value, and scholars agree that comprehensive site planning and human action restrictions explain a pregnant part of their loftier value today. In doing and then, Nichols's innovations have helped brand permanent the deep setbacks and cul-de-sac urbanism that defines suburbia.

Nichols's vision for landscape blueprint prepare his subdivision apart from the "ordinary way." Information technology likewise laid the background for the legal and managerial codes that would regulate future development and land use on the site. The curving streets that follow the topography, triangular mini-parks that ease traffic flow at intersections, and attention to landscaping created a visual tableau that attracted buyers and provided copy for newspaper ads. From Nichols'south white-washed, neo-colonial sales outpost, potential buyers could survey the mural and imagine stately homes and mature trees behind each sidewalk. And with the assurances of the deed restrictions and home owners' associations, buyers were insulated from the risks of a volatile existent estate market place.

Understanding J.C. Nichols's role in the early on decades of the 20th century in Kansas City sheds low-cal on how the shape of Kansas City informed broader patterns of suburbanization in the U.s.a.. Nichols would go on to shape federal policy as the founding president of the National Association of Dwelling Builders. Nichols'south deed restrictions were the model that the Federal Housing Administration would recommend other developers to follow in The Customs Builder'south Handbook in 1947. Through this document and other disseminations, the subdivisions he built in Kansas City influenced subdivisions across the continent. But more than than this, studying Nichols sheds light on how real estate developers saw the relationship between city and suburb, and between private market controls on development and the public powers of urban center planning. Considering Nichols'southward explicit linking of aesthetics and market economics, the aesthetics of suburbia depended as much on cultural constructions of the picturesque every bit they did on managing the risks of the market.

0 Response to "Paul Eade Kansas City Country Club Plaza Art Gallery"

Post a Comment